Jane Freeman paints, among other things, illustrations for classic novels.

A novel may work on us like a lucid dream. Awake, but not in control of events, we take in images, words, symbols, ideas, feelings, without pausing to master them--and they work their way in our interior world, pressing secret latches and opening previously unsuspected doors.

One pleasure of childhood I’ve always been sorry to leave behind is the illustrated story. Like Jane Eyre, in adult books I saw “no bright variety … spread over the closely-printed pages” and felt a blank loss. But most attempts to illustrate novels, especially beloved novels, have left me cold. Their literal approach clashes painfully with my interior visions; I’m unable to pour into them my own responses to the work. This dull-looking lady of flesh and blood in h er over-elaborate clothing and hair can’t be my Jane Eyre, my Lizzie Eustace, my Marian Halcombe! My imagination slides away from the images instead of entering and giving them life.

er over-elaborate clothing and hair can’t be my Jane Eyre, my Lizzie Eustace, my Marian Halcombe! My imagination slides away from the images instead of entering and giving them life.

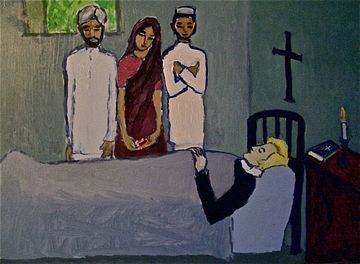

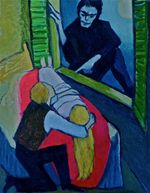

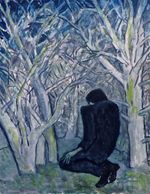

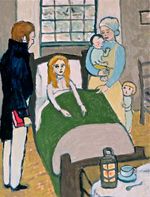

Hence my enthusiasm for these small paintings by Jane Freeman for Jane Eyre, Frankenstein, and Persuasion. They are visual delights, but that’s not the real reason I keep coming back to them. These doll-like beings have life and expression to draw me in, but not so much independent reality as to repel me with their otherness. Viewing them, I inhabit them, invest them with my own life, my own meaning. The expressionistic qualities

of the paintings, often extreme, might, I suppose, run the risk of over-

of the paintings, often extreme, might, I suppose, run the risk of over-

interpreting the writing. But this doesn’t happen; perhaps the level of visual abstraction imposes a restraint that leaves space for my dreaming mind to do its work along with the artist’s.

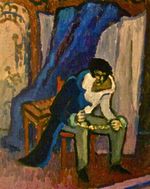

The paintings are informed by an intense study of the works that inspired them, which comes out in many ways, often in sly touches like the red book in the scene from Chapter 14 of Persuasion, or the mirror behind Sir Walter in Chapter 16. My imagination is stimulated, too, by considering the choice of which moments to illustrate. Why show Mr. Rochester miming the prisoner in Bridewell

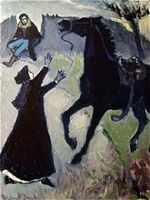

in the scene from Chapter 14 of Persuasion, or the mirror behind Sir Walter in Chapter 16. My imagination is stimulated, too, by considering the choice of which moments to illustrate. Why show Mr. Rochester miming the prisoner in Bridewell , for instance? Only when I asked myself this question did it occur to me that what I had always considered a superfluous scene presented in quite unnecessary detail was in fact part of what Freeman calls the “narrative as solid as a crown” of Jane Eyre. Rochester is indeed a prisoner of his marriage to Bertha Mason, of whom his mock-bride Blanche Ingram is an avatar. The scene is part of Brontë’s obsessive patterning of allusions and foreshadowings.

, for instance? Only when I asked myself this question did it occur to me that what I had always considered a superfluous scene presented in quite unnecessary detail was in fact part of what Freeman calls the “narrative as solid as a crown” of Jane Eyre. Rochester is indeed a prisoner of his marriage to Bertha Mason, of whom his mock-bride Blanche Ingram is an avatar. The scene is part of Brontë’s obsessive patterning of allusions and foreshadowings.

Then, too, these figures I’ve called doll-like can be amazingly expressive of physical and emotional movement: for instance the “Off, ye lendings!” illustration from Chapter 19 of Jane Eyre and (particular favorites) both the illustrations for Chapter 24 . I can’t explain to myself why there’s a strong mixture of affectionate laughter in my response to this expressiveness. Maybe it’s the miniature quality of the scenes. They are real, serious, and tiny.

. I can’t explain to myself why there’s a strong mixture of affectionate laughter in my response to this expressiveness. Maybe it’s the miniature quality of the scenes. They are real, serious, and tiny.